Today's solution to yesterday's deal: managing difficult contracts, part 1

Some problems with a contract can be caught before they even happen, and can be managed proactively to keep the project on track.

As governments and private companies look at more outsourcing and service contracts, their performance becomes more dependent upon the performance of their contractors. This is, however, old hat for the construction industry, where managing contracts has long been crucial to the success of a project.

In this two-part article, we'll first set out what we've learnt from our years in major projects about managing contracts actively and effectively – and then look at what you can do when things have gone beyond the point where ordinary management is going to work.

The first rule for managing difficult contracts is to solve small problems before they turn into big ones.

If you wait until the problem has run up a million dollars in cost overruns, both sides will be afraid of admitting any fault for fear of being stuck with the whole liability. At the front end, it is much easier to have honest, objective and productive discussions with the contractor.

That's easily said, but how do you catch small problems before they grow?

Understand the contract

Some problems can be caught before they even happen.

If you have managed any similar contracts before, and even if you haven't, there will be some areas of the contract that you can anticipate will potentially cause problems. Friction often arises at the interfaces between you and the contractor.

Submissions for approval are the most obvious, but there are many other possible interfaces: you may be rolling out software at different locations, carrying out community consultations for multiple worksites, accepting regular deliveries of particular product. Any process that will be repeated many times will cause a lot of trouble if you get it wrong.

One very common scenario in project contracts is for the contractor to be required to submit plans and designs for approval before it can get on with construction. On a large project there may be dozens or even hundreds of submissions. If there are a hundred submissions and each one takes a week longer to approve than was in the plan, that is two years’ worth of delayed activity. While submissions will to a greater or lesser extent be delivered in parallel, the cumulative delay is likely to push the project into trouble.

Don't even wait for the first submission. Sit down with the contractor and agree to run the first submission as a pilot, and then set up a continuous improvement process. Good collaboration doesn’t happen by accident – you need to work at it.

Doing this early in the process means it's much easier for both parties to be honest with each other. There will quite likely be faults on both sides. It is always important to give serious consideration to the possibility that the principal might be the one at fault. If your own house isn't in order it is really difficult to hold the contractor to account.

Use the governance framework

Where both parties are actively involved, it is easy to see what is happening and pick up on problems early. When only the contractor is aware of potential issues, however, it can be much harder to get visibility. This is why you should make use of the governance provisions in the contract, which can include:

- regular meetings with the contractor;

- regular reports;

- a right for you or a third party to conduct audits of their project accounts and/or activities;

- a right to demand a cure plan if there is a breach of contract.

If you are active in managing the contract you can often secure all of these things, even without a specific provision in the contract.

Meetings

Meetings are important. When the parties don't communicate, trouble ensues. But you do have to prepare for them.

Have an objective for each meeting and start the meeting by agreeing that objective with the contractor: "today we want to identify the root causes of problem x".

Then stop the discussion just before the agreed closing time and ask "have we achieved our objective and if not, what will be done about it?” If you just let the meeting run on until people leave, not only have you not solved the problem, you don’t have an agreed set of next steps.

Often the problem is that the contractor's project director is under so much pressure from their superiors to stick to a budget that they don't want to ask for the extra resources it would take to do the job properly. They may not want to admit to problems because of the personal consequences, or they are just too junior to be heard.

In this situation you must take the meetings to a higher level of seniority. Quite often a contract will provide for CEO one-on-ones as part of the dispute resolution mechanism, or the CEO might want to keep it on a more informal basis.

CEO meetings won't solve the problem if the contractor’s CEO is being given a false picture by their own project team. To change the behaviour you need facts and evidence. Use your other governance tools of reports and audits to find the facts, then give your CEO the ammunition to present in a way that can't be ignored.

Do not fall into the trap of minimising your own part in the problem by concealing your own failings. If your CEO is confronted in the meeting by unexpected evidence that you are at fault, even if only partially, you will not only have a very unhappy CEO, you will lose all traction in managing the contractor.

Reports

The contract will give you rights to receive reports. These should be in a format that will be informative while not requiring an enormous effort in production.

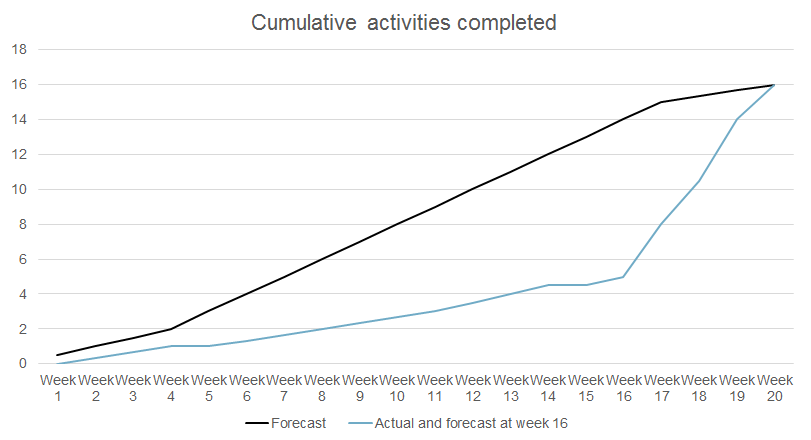

The most useful reports do not merely tell you what is happening, but also show the gap between what has been achieved and what was supposed to have been achieved during the period. Visual representations can be very powerful: one useful tool is the S-curve.

Suppose there are 16 activities that need to be completed by the contractor (the activities don't have to cover the whole contract activity, and with large contracts often it's better if they don't). The plan says it will take two weeks to do each of the first two, then they'll be done at the rate of one a week, except for the last one, which will take three weeks.

These charts can be about activities completed, or money spent, or milestones achieved. Theoretically, if the contractor doesn't do anything different, then each day's delay pushes the line a day to the right, but in practice reports typically show the same end point but a steeper line on the graph.

In the illustration shown, the contractor is, at Week 16, suggesting that activities originally programmed to take 13 weeks will take just four – highly implausible. But if the S-curve is being examined regularly, the gap between forecast and actual is already visible ten weeks earlier. This offers an opportunity to ask the contractor what it will do differently to close the gap, increasing the chance of the problem being solved before it gets out of hand.

The contractor may point to contingency in the schedule, or propose additional measures such as putting in a shift on Saturdays or recruiting an extra work team. That allows you to consider how plausible those proposals are and gives an objective basis for starting productive discussions.

Audits

Independent audit reports can be very effective. When the relationship has essentially broken down, it is often easier for the parties to discuss a third party report than to accept representations from the other, particularly when the contractor refuses to admit there is a problem.

One of the authors (Louise Hart) has personal experience of a contractor who kept insisting that there were no problems with delivery: some things were "a bit late", but they were able to adjust the schedule for that, and so on. Eventually an independent third party was sent in to audit the schedule.

The audit report showed the project was so far behind that the final delivery date was now further away than it had been on the day the parties signed the contract. The independent report forced the contractor to admit the problem.

So, if you suspect there is a problem, think about sending in auditors. Look for objective, measurable facts that you can confront the contractor with.

Audit reports also help with your own stakeholders. Some of the more radical remedies discussed in Part 2 often require permission from senior management, and an independent audit is much more convincing than a mere complaint.

Cure plans

Contracts will often oblige a contractor to provide a cure plan when it is in default.

Cure plans do not have to be formal. In the schedule audit example above, a formal cure plan was not demanded from the contractor as it was arguable there was technically no default at that point. Instead, the contractor was asked what it proposed to do to remedy the situation.

Sometimes this is enough to get some action. Sometimes it isn’t. In that case the contractor produced a list of things it wanted the principal to do differently. Conspicuous by its absence was any proposal involving action by the contractor.

In response, the principal wrote a strong ‘letter before action’ to the contractor's chief executive, which resulted in the contractor's project director being replaced by a more co-operative individual, enabling a negotiated solution to be reached.

Changing a project director is not necessarily the solution – any project which has had more than two project directors is normally a project in trouble – but if the director is the problem, they should be removed.

A less drastic course of action to encourage cooperation from an uncooperative contractor is to set up a workshop or series of workshops with a third party facilitator.

This became part of the way forward on Louise's difficult contract, but only after the project director was replaced. Key members of the project teams went on an awayday with a third party facilitator and came up with various ways of improving collaboration between the parties without altering the contractual rights and obligations.

There is an important caveat. While third party facilitation can be effective with the right facilitator, one who properly understands the contract and has the trust of the parties, but the wrong facilitator may be worse than useless.

It is too easy for a third party to look at a situation and decide that life would be simpler if the contractor didn't have to comply with the contract. Working collaboratively does not have to mean giving up your contractual rights.

Beating a jinx

Some projects are just ill-fated. If you get caught in one of those, the only solution is extreme micromanagement. Prepare every detail, agree actions, give instructions, assume that nothing will be done properly unless you check everything, every time, every day.

That includes your own team, not just the contractor. A contractor in trouble will do their best to deflect blame to you and you must avoid giving them grounds to do so. If you have to respond to something in five working days, check on progress every day, not just day five.

You must be absolutely relentless, with your own team and with the contractor. If the contract is jinxed, you have to take action every single day.

And if none of that works, there's always a legal remedy.

Louise Hart is an independent consultant specialising in major projects and procurement. Her forthcoming book, Procuring Successful Mega-Projects: How to establish major Government contracts without ending up in court, will be published by Gower Publishing in September 2015.

You might also be interested in...