Public Law Essentials: Artificial intelligence

Artificial intelligence (AI) is a broad term with no universally agreed meaning. In simple terms, AI is technology that enables machines (particularly computer systems) to perform tasks that would normally require human intelligence, such as reasoning, decision-making, and problem-solving.

Many Government AI policies and frameworks in Australia adopt the OECD’s definition of an “AI system” (revised as at November 2023):

“A machine-based system that, for explicit or implicit objectives, infers, from the input it receives, how to generate outputs such as predictions, content, recommendations or decisions that can influence physical or virtual environments. Different AI systems vary in their levels of autonomy and adaptiveness after deployment.”

Common AI terms

- Algorithm: Rules that a machine can follow to perform a task.

- Automation: The degree that a system acts without human intervention or control of some kind. Automation overlaps with AI, but is a distinct concept.

- Machine learning: The primary approach to building AI systems. Machine learning uses algorithms that learn from data to make predictions, without the need to be explicitly programmed to do so. The system mimics the human learning process, and learns over time, from data and experience, how to progressively get better at making predictions.

- Deep learning: A subset of machine learning that is based on a more complex and less linear structure of algorithms, and modelled on the human brain. These algorithms enable the processing of unstructured data, and can make connections and weigh input by learning from data.

- Generative AI: Algorithms that are capable of generating new content (such as text, images, audio, and codes), as well as categorising and grouping content, in response to a user’s prompt or request. The system relies on deep learning models to identify patterns within datasets.

- Natural language processing (NLP): Concepts of computer science, linguistics, machine learning, and deep learning that are combined to teach a computer to understand and communicate with humans.

AI use in the public sector

AI adoption across corporate and Government sectors continues to increase, alongside the rapid growth in AI technology development.

For the Government sector, the benefits of adopting AI can include more efficient and accurate operations, resulting in improved service delivery to, and better outcomes for, the Australian community. Example of AI capabilities currently being used in ICT solutions across agencies include:

- chatbots and virtual assistants in service management;

- the automation and streamlining of routine back-room administrative processes and tasks;

- document and image detection, and recognition (for example, in a law enforcement or fraud detection settings); and

- NLP technology, including free text recognition and translation functionality.

AI regulation in Australia

There is currently no AI-specific legislation in Australia. However, there is a large body of law (both legislation and common law) that can apply to AI use, including:

- privacy laws where personal information is involved;

- civil laws relating to contract, negligence and defamation where AI produces information or other outputs that are incorrect or harmful;

- intellectual property (IP) laws, where data input and AI outputs may be subject to IP rights;

- anti-discrimination and employment laws (amongst others), where AI produces outputs that are biased; and

- administrative law where AI is applied and produces outputs in a way that does not align with administrative decision-making principles (discussed in more detail below).

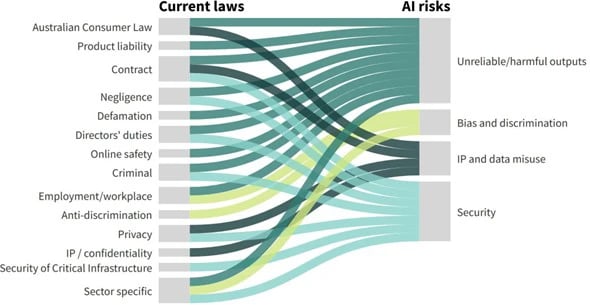

Key AI risks & harms, and current laws

Standards, policies, guidelines and other frameworks

There are a number of resources (current and developing) to assist public sector bodies to identify and manage potential risks, and to build public trust, when contemplating and implementing AI systems. These include the following key frameworks:

AI Ethics Framework and Principles

A voluntary framework of eight principles (summarised below) aimed at assisting both Australian businesses and Government agencies to incorporate ethical practices into, and reduce the risks associated with, the design, development, and implementation of AI systems.

- Principle 1 (Human, societal and environmental wellbeing): AI systems should benefit individuals, society, and the environment. Systems should not create outcomes that cause undue harm.

- Principle 2 (Human-centred values): AI systems should respect and preserve human rights, diversity, and the autonomy of individuals.

- Principle 3 (Fairness): AI systems should be inclusive and accessible, and should not involve or result in unfair discrimination against individuals, communities or groups.

- Principle 4 (Privacy protection and security): AI systems should respect and uphold privacy rights and data protection, and ensure the security of data.

- Principle 5 (Reliability and safety): AI systems should reliably operate in accordance with their intended purpose.

- Principle 6 (Transparency and explainability): There should be transparency and responsible disclosure about AI systems, so individuals can understand when they are being significantly impacted by AI, and can find out when an AI system is engaging with them.

- Principle 7 (Contestability): When an AI system significantly impacts a person, community, group or environment, there should be a timely process to allow people to challenge the use or outcomes of the AI system.

- Principle 8 (Responsibility and accountability): Those responsible for different phases of the AI system lifecycle should be identifiable and accountable for the outcomes of the AI systems, and human oversight of AI systems should also be enabled.

Policy for the Responsible Use of AI in Government

This policy seeks to ensure a unified approach to safe, ethical, and responsible use of AI by Government in line with community expectations, and requires entities to:

- nominate one or more accountable officials by 30 November 2024 (and notify the Digital Transformation Agency of the nomination(s)); and

- publish an AI transparency statement by 28 February 2025 (and provide a copy to the DTA).

The policy is mandatory for non-corporate Commonwealth entities. It does not apply to corporate Commonwealth entities, nor to the use of AI by the Defence portfolio or the national intelligence community, although elements of the policy can voluntarily be adopted (ie. where national security capabilities/ interests are not compromised).

National Framework for the Assurance of AI in Government

Aligned with the AI Ethics Principles, the framework:

- aims to achieve a nationally consistent approach to the safe and ethical use of AI by Government across all levels; and

- establishes five key cornerstones and practices (Governance, Data Governance, Risk-based Approach, Standards, and Procurement) to help lift public trust in the adoption of AI technology by Government, and ensure AI technologies are used ethically and responsibly.

Voluntary AI Safety Standard

Practical guidance for all Australian organisations on how to safely and responsibly use AI. It includes 10 guardrails (summarised below) that apply to the development and deployment of AI in high-risk settings, throughout the AI supply chain.

- Establish, implement and publish an accountability process including governance, internal capability and a strategy for regulatory compliance.

- Establish and implement a risk management process to identify and mitigate risks.

- Protect AI systems, and implement data governance measures to manage data quality and provenance.

- Test AI models and systems to evaluate model performance and monitor the system once deployed.

- Enable human control or intervention in an AI system to achieve meaningful human oversight.

- Inform end-users regarding AI-enabled decisions, interactions with AI and AI-generated content.

- Establish processes for people impacted by AI systems to challenge use or outcomes.

- Be transparent with other organisations across the AI supply chain about data, models and systems to help them effectively address risks.

- Keep and maintain records to allow third parties to assess compliance with guardrails.

- Engage your stakeholders and evaluate their needs and circumstances, with a focus on safety, diversity, inclusion and fairness.

NSW Artificial Intelligence Assessment Framework

A mandatory risk self-assessment framework for NSW Government agencies when designing, developing, deploying, procuring or using AI systems, which is designed to align with the five AI Ethics Principles outlined in the NSW Government Policy Statement, and Circular DCS-2024-04 (Use of Artificial Intelligence by NSW Government Agencies). This framework may be of use to Commonwealth and other state/ territory Government agencies, as it was also used as a baseline to develop the National Framework for the Assurance of AI in Government.

AI risk management

There are many complex legal and ethical issues that can arise in relation to AI and its application in particular use cases. If risks are not effectively managed, this can have a range of potential implications and consequences for the agency and others, including for example:

- decisions or outputs that lead to harmful or negative outcomes;

- data validity and reliability;

- non-compliance with legislation and other legal obligations;

- improper interferences with privacy;

- compromised system and data security;

- impacts on critical infrastructure and agency assets; and

- damage to agency reputation and public trust.

Further, the nature and scale of risks and harms may not always be known from the outset, or may change over time. It is therefore important for agencies to assess risks at all stages of an AI project, and throughout the lifecycle (design, development, deployment, procurement and use) of solutions that incorporate AI components.

Key elements of an AI legal risk management strategy include (but are not necessarily limited to) the following:

- understanding legal and regulatory requirements, and monitoring developments;

- implementing AI and data governance arrangements, including clear lines of accountability;

- staff training;

- undertaking privacy, security, ethical and AI impact assessments for AI projects;

- testing of AI systems before deployment, with ongoing monitoring and auditing;

- ensuring transparency in the use of AI (eg. policies and notices), and its application in particular instances (eg. audit trails);

- consent management; and

- vendor and third party management.

AI use in automated administrative decision-making

Risks of AI systems in automated decision-making

AI and automated decision-making are different concepts. While an AI system can be used for automated decision-making, not all AI systems and uses cases involve automated decision-making (and vice versa).

AI automation systems have the potential to produce benefits such as improving consistency, accuracy, transparency and timeliness in decision- making. Because automated decision-making systems are based on logic and rules, they generally lend themselves better to decisions that can be objectively determined on matters of fact.

However, many administrative decisions require the exercise of discretion or evaluative judgment, such as determining whether a person is of “good character” or “has a reasonable excuse”. These complex assessments may not be adequately addressed by rigid, rules-based systems, and may raise concerns about fairness and the risk of legal error, for example:

- bias in AI algorithms (and the datasets that AI models are trained on), resulting in unfair outcomes;

- inflexible application of policy where an AI system makes a discretionary decision based on rules that reflect predetermined guidelines or policy criteria, without regard to all of the available information and a person’s circumstances;

- identifying relevant and irrelevant considerations, and that appropriate weight is given to relevant factors; and

- ensuring procedural fairness, including where an AI system is making a decision based on adverse information obtained from a third party source, or generates adverse information that may materially impact on the decision outcome.

Case studies

The risks of the use of AI systems in administrative decision-making processes, and the issues in terms of legality of the decisions made, have been the subject of some judicial consideration. Here, we look at two key cases.

Pintarich v Deputy Commissioner of Taxation [2018] FCAFC 79

The Court held that a decision-made by a computer algorithm did not constitute a valid “decision” made by the Deputy Commissioner of the ATO (as required by the relevant legislation), on the basis that: (a) a valid “decision” requires both a mental process of reaching a conclusion and an objective manifestation of that decision; and (b) no such mental process took place when the ATO delegate generated the letter from the computer-based system. In this case, the delegate had merely input information into a computer-based “template bulk issue letter”, and failed to review the content before the “decision” letter was issued to Mr Pintarich.

This case raises broader issues around the increasing use of automated decision-making systems, which challenge the traditional expectation that decisions involve human mental processes. Justice Kerr, in his dissent, noted that technology is now capable of making complex decisions without human input, and that the legal concept of what constitutes a “decision” may need to adapt to this reality.

The judgment in Pintarich also underscores the need for human oversight to ensure significant decisions, particularly those with material impacts on individuals or organisations, are appropriately made and communicated. As automated systems become more widely used, finding the right balance between efficiency and oversight will be crucial.

Schouten v Secretary, Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations [2011]

This case involved an applicant who sought a review of the amount of Youth Allowance benefit payable to them, which was calculated by an automated process.

While the calculation was ultimately affirmed by the Tribunal as correct, the Tribunal noted that it was only during the hearing when a Department officer provided evidence about an automated process used to calculate the rate of a benefit, that the Applicant (and the Tribunal, itself) was able to understand the process utilised to arrive at the calculation in question. The Tribunal emphasised the challenges that arise when Government agencies rely on automated decision-making processes, particularly for complex decisions, noting individuals may struggle to understand or challenge such decisions without a clear, plain-English explanation of the basis for the decision.

For agencies, this case highlights the need for automated systems to generate comprehensive audit trails that link the decision-making process with applicable rules and facts, ensuring transparency, enabling checks and reviews, and allowing external scrutiny. The case also highlights the importance of ensuring automated decision- making processes comply with the AI Ethics Principles, particularly those relating to decision transparency and contestability.

Checklist: Considerations for implementing and using AI systems in administrative decision-making

Agencies should proceed with caution and seek legal advice to understand the legal risks and implications before implementing (AI or other) automated systems for administrative decision-making. The following are some key questions agencies should turn their mind to when designing and implementing automated decision-making processes:

Who?

- Does the legislation specify who can or must make the decision? (For example, does the legislation authorise the use of a computer to make the decision, or require the decision to be made personally by a particular person or authorised delegate?)

Automation

- How is automation being used in the context of the decision? (For example, is it being used for the whole or part of the decision-making process; to guide a decision-maker through the relevant facts and provide support systems; to provide a preliminary assessment or recommendation for the decision- maker to consider?)

Deciding factors

- What factors does the legislation require to be taken (or not taken) into account when making the decision?

Discretion or judgment

- Does the legislation require the exercise of discretion or judgment by the decision-maker?

Compliance

- Does the process comply with relevant administrative law principles (legality, fairness, rationality and transparency), and provide access to reviews, dispute resolution processes, and investigations of the decision?

Transparency

- Is the automated process explainable and transparent?

Key take-outs

- Identify the issue that you want to address, and determine whether AI is the most appropriate solution.

- Proceed with caution when designing and implementing AI in an automated decision-making context, particularly where decisions involve the exercise of discretion.

- The risks of using AI and potential mitigation strategies must be considered from an agency governance level. It is important for agencies to ensure a positive risk culture, and to promote open and proactive AI risk management as an intrinsic part of everyday practice.