Birkenstock shows that it is possible to secure trade mark protection over the shape of popular product designs

Stopping others from copying your product designs is a perennial problem, particularly for those in the fashion industry. In Australia, protection for the design of products such as footwear is normally obtained through the registered designs system. However, Birkenstock is seeking to protect its footwear designs using trade mark registrations. This article examines how Birkenstock can protect its popular shoe designs using shape trade mark registrations and why trade mark protection over its designs might be preferred over other forms of IP protection.

Birkenstock’s shape trade marks

The Australian Trade Marks Office (ATMO) has recently published a decision by which several Birkenstock shape trade marks were accepted for possible registration.

Birkenstock already had a trade mark registration for its iconic "Arizona" sandal shape as shown below:

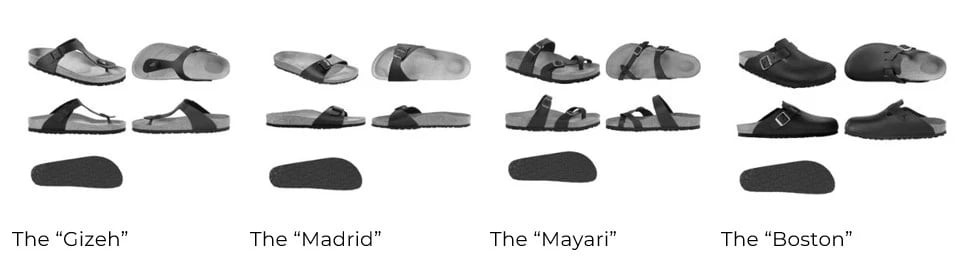

In this recent decision, Birkenstock has also now achieved acceptance for some of its other popular styles shown below:

How did Birkenstock obtain trade mark protection over the “shape” of shoes?

Trade mark applications – whether they be for words, logos, shapes or anything else – will be rejected if they are not capable of distinguishing the goods or services of one trader from the similar goods or services of another. In essence, this is determined by asking whether the trade mark is something which other traders are likely to want to use on or in connection with their similar goods.

As you might expect, many shape trade mark applications are met with a distinctiveness objection, such as on the basis that the application claims footwear and the trade mark is in the shape of a shoe which other traders would want to use – including due to its functional aspects. In order to achieve acceptance, brand owners then need to file evidence of their extensive use of the trade mark to demonstrate that consumers have, in fact, come to associate the shape with their particular business, despite the lack of inherent distinctiveness.

In Birkenstock’s case, the ATMO was willing to grant acceptance over these shape trade marks because, despite having a functional aspect, the shapes of the shoes were somewhat distinctive. Notable features included:

- a wide footbed and thick outer and inner sole, creating a "chunky" aesthetic;

- the thickness of the straps adding to the "chunky" appearance;

- large square buckles on the straps;

- a moulded sole which included toe bars, footbed rims and heel cups;

- a "squiggly" grid pattern on the outer sole; and

- the silhouette or outline of the footwear.

There was also evidence of long-time use, significant promotion, celebrity endorsement, and the manner in which the marks were used. This included the fact that footwear is typically sold in stores displaying the goods so consumers are exposed to the footwear itself (and are not, for instance, immediately exposed to an accompanying word trade mark).

Birkenstock also applied to register the shapes of its "Florida" and "Zurich" styles, but was not successful due to the low levels of sales of those styles.

Trade mark versus design protection

Birkenstock’s case highlights the potential for trade mark law to be used as a tool by brand owners (and their licensees) to stop third parties from copying their valuable product designs and maintain exclusivity in the market.

In Australia, there are many different types of “signs” which can be registered as a trade mark, including words, logos, colours, sounds, scents and “shapes”. Usually, the scope of protection over the “shape” will be defined by the shape as depicted in representations or images attached to the trade mark application form, which will appear on the Trade Marks Register.

While shape trade marks are not as common as word or logo trade marks, there are currently 1,255 registered shape trade marks on the Australian Trade Marks Register. There are a number of footwear shape trade marks that are registered, owned by companies such as Crocs, Superga and R. M. Williams. Examples of other registered shape trade marks relate to the shape of beverage and perfume bottles, bags, toys, chocolate, biscuits, pens and vehicles.

It is generally very difficult to secure registration of a shape trade mark. However, Birkenstock’s case shows that it is very much possible to do so where sufficient evidence is available.

Applying for a design registration can be an easier and less costly option. Designs can provide exclusivity in relation to one or more visual features of a product. Their validity is not assessed by reference to any “distinctiveness” test, but merely need to be new and distinctive compared with what has gone before.

However, a drawback of registered designs is that they only provide protection for a maximum of 10 years. Trade mark protection is a better option in that respect as trade mark registrations can be renewed indefinitely. For example, Weber Barbeques owns shape trade mark registrations which are still valid and enforceable, despite having been filed almost 30 years ago.

Overall, when seeking to protect their product designs, brand owners and designers have a number of different options available. However, Birkenstock’s recent success shows that shape trade mark registrations should be considered in appropriate cases, and can be a very effective way to stop copycats in their tracks.

Get in touch