Two Bored Apes walk into an NFT marketplace… and test the limits of intellectual property rights

The Yuga case raises interesting questions regarding IP rights in the emerging web3 space, where NFTs are now prevalent.

Yuga Labs Inc., the blockchain technology company that specialises in developing digital collectables, has recently commenced court proceedings against artist Ryder Ripps over the sale of alleged copycat NFTs. Yuga is the company behind the Bored Ape Yacht Club NFT collection, one of the most popular and valuable collections in the NFT space (for example, last year 101 Bored Ape NFTs resold for $24.4 million at an auction).

Ripps, on the other hand, is a self-proclaimed “conceptual artist” notorious for his controversial satirical projects, who allegedly made $1.8 million off the alleged copycat collection of the Bored Apes. While the lawsuit has been filed before the Central District of California and will be decided under US law, it raises important questions about how Australian trade mark law might deal with a similar NFT trade mark dispute.

Ape NFTs go into legal battle

The case stems from a collection of NFTs called the Ryder Ripps Bored Ape Yacht Club. Yuga is claiming that Ripps promotes and sells the Ripps NFTs using the same trade marks that Yuga uses to promote and sell its authentic Yuga NFTs. According to Yuga, this conduct is causing confusion amongst consumers and a decline in value of the authentic Yuga NFTs.

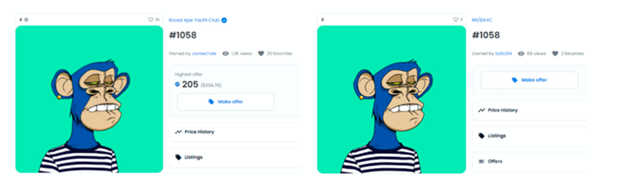

To get a sense of the similarity between the digital works, the example below shows an official Yuga NFT on the left, and the “corresponding” Ripps NFT on the right:

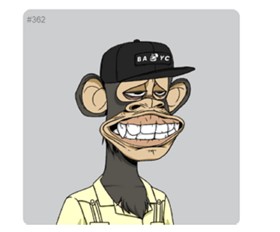

In another of the Ripps NFTs, the digital art contains the “BAYC” logo on the avatar’s cap:

The similarity, at least on initial view, is stark. This is particularly so given that they are sold on the same NFT marketplaces.

However, Yuga does not own any registered US trade marks. It is instead relying on a number of pending US trade mark applications for trade marks that it claims to have used since at least April 2021 (the BAYC Marks). Although they have not yet been accepted by the USPTO, the applications include:

- BAYC;

- BORED APE; and

- BORED APE YACHT CLUB.

Yuga is therefore relying on its common law (unregistered) trade mark rights. However, enforcing common law trade mark rights can be very difficult.

Yuga is also relying on its significant use of the BAYC Marks in connection with advertising, marketing and promoting the Yuga NFT collection, both nationally and internationally. Yuga claims its presence on multiple platforms, including NFT markets and social media, has resulted in significant goodwill for the BAYC Marks.

Unregistered trade mark rights in Australia

As noted above, Yuga is relying on its unregistered trade mark rights in the US. In Australia, unregistered trade marks can be protected through a claim for passing off, or for misleading conduct under the Australian Consumer Law. Passing off can protect the goodwill which has been developed in unregistered trade marks (or even other “trade indicia”, such as the appearance of the Yuga NFT images) by virtue of their extensive use. If Yuga were to bring such a claim in Australia, there are three elements it would need to establish:

- Goodwill: has Yuga established goodwill / a reputation in the appearance of the Yuga NFTs / BAYC Marks?

- Misrepresentation: are consumers likely to be deceived to believe that the Ripps NFTs emanate from, or are approved by or associated with, Yuga?

- Damage: has the above misrepresentation harmed, or is it likely to harm, Yuga’s business or reputation?

If Ripps engaged in this conduct in Australia, it would certainly be open to Yuga to bring a claim for passing off. Such a claim is invariably brought in conjunction with a claim under the Australian Consumer Law. That legislation prohibits (among other things) misleading or deceptive conduct, or the making of false representations regarding sponsorship, approval or affiliation. It is important to note that a person can contravene those prohibitions, even where they do not have an intention to mislead or deceive. Therefore, whether Ripps intended to “critique” Yuga through its NFTs (as described further below) is irrelevant – the key question is whether the overall impression created by Ripps’ conduct would lead consumers into error.

What if Yuga had registered trade marks?

If Yuga owned trade mark registrations for the BAYC Marks, the claim could be brought for the infringement of those trade mark registrations.

A claim for registered trade mark infringement is, in most circumstances, far easier to establish than a claim for passing off or under the Australian Consumer Law. That is because, to succeed in an action for registered trade mark infringement, it is not necessary to prove that you have developed any reputation or goodwill in respect of that trade mark. The Certificate of Registration does that work for you.

In addition, a trade mark registration can be highly valuable. A trade mark registration is a separate asset which has its own value and can be assigned, sold or purchased. An unregistered trade mark is not a separate asset of a business – it is specifically tied to the goodwill of the business and cannot be separated from it.

If Yuga owned such registrations in Australia, it would still need to demonstrate that Ripps had been using those (or similar) trade marks “as a trade mark”. This requires the trade mark to be used as a “badge of origin” – ie. to identify the trade source of the goods or services.

Ripps' response

In his response, Ripps has relied on artistic free speech, arguing that his NFT project was a “critique” of Yuga’s work.

In Australia, the Federal Court has held that where a party modifies a trade mark for satirical purposes, or uses it as the subject of criticism, the trade mark may not have been used “as a trade mark” for infringement purposes. However, given that the BAYC Marks have not been altered in the Ripps NFTs, and the Ripps NFTs (on their face) have not obviously been created for the purpose of criticism, it would be difficult for Ripps to rely on that argument here.

As Yuga set out in its complaint:

“Brazenly, he promotes and sells these RR/BAYC NFTs using the very same trademarks that Yuga Labs uses to promote and sell authentic Bored Ape Yacht Club NFTs. He also markets these copycat NFTs as falsely equivalent to the authentic Bored Ape Yacht Club NFT.” [emphasis added]

What about copyright?

Where someone is reproducing an image or drawing in which you own copyright, the best angle of attack would normally be a claim for copyright infringement. However, we understand that Yuga decided not to bring a copyright infringement claim in this case because the Yuga NFT images are generated by a computer algorithm, rather than a human author. If that were not the case, we expect that a copyright infringement claim would be at the tip of Yuga’s spear.

Final thoughts (and questions) on NFTs

The Yuga case raises interesting questions regarding IP rights in the emerging web3 space, where NFTs are now prevalent. For example, would “use” of a trade mark on a virtual platform in association with a tokenised “asset”, such as Decentraland, be treated the same as use of that trade mark in the physical world? And would use in the borderless virtual world constitute use in all (or any) jurisdictions? Hopefully some clarity will be provided when cases come before the Australian courts which address these issues. As to the Yuga case, we will monitor its progress and provide an update once judgment is delivered.

Get in touch