Mind the gap: High Court expands the reach of case management

The last two decades have seen a cultural shift in the conduct of civil litigation. Case management principles have taken centre stage as the legal system strives to address challenges of cost, delay and inefficiency. The "overarching purpose" set out in section 37M of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) mandates the just resolution of disputes according to law as quickly, inexpensively and efficiently as possible. Similar provisions exist in all Australian States and Territories.

Cases over the past 20 years provide guidance about the range of conduct which might offend the overarching purpose. In a recent case the High Court applied case management considerations to punish conduct that Justices Nettle and Edelman (dissenting) described as "common sense" and Justice Gordon (also dissenting) described as "not unreasonable". The majority's decision operated to strip a litigant of substantive legal rights, highlighting the need for caution: UBS AG v Tyne [2018] HCA 45.

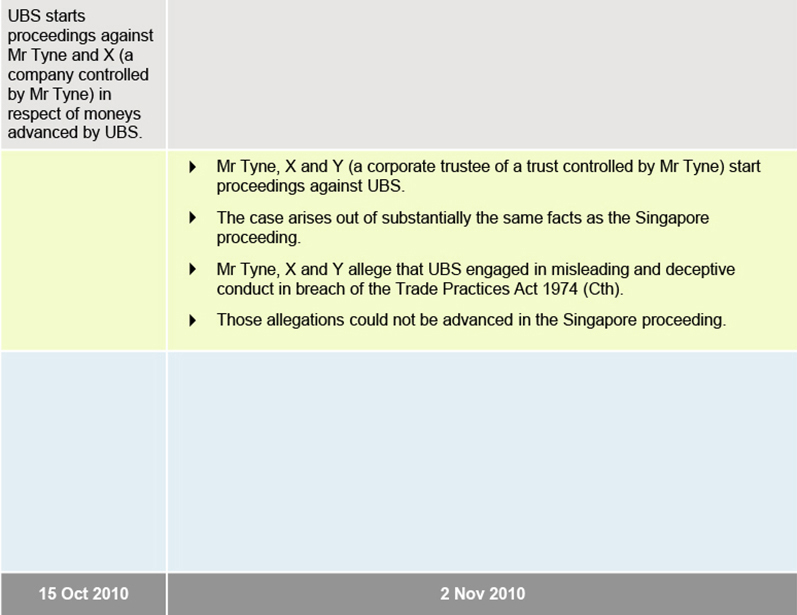

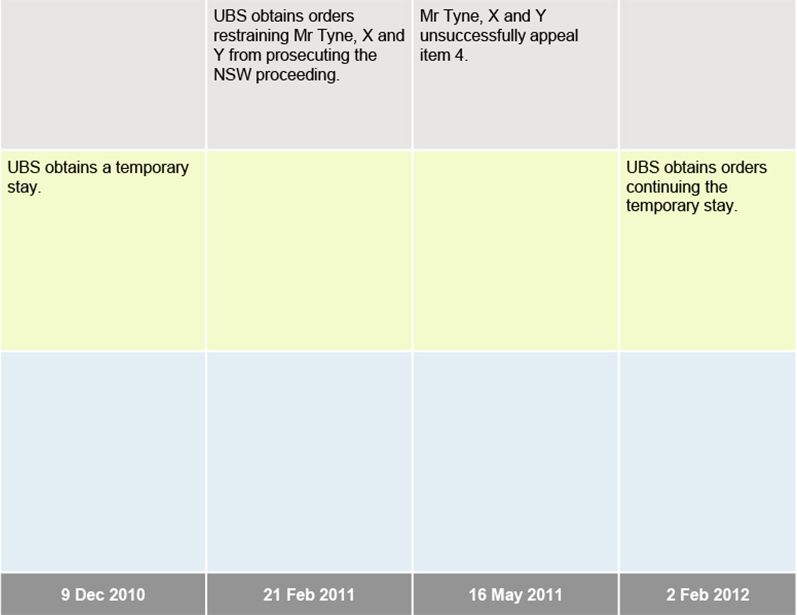

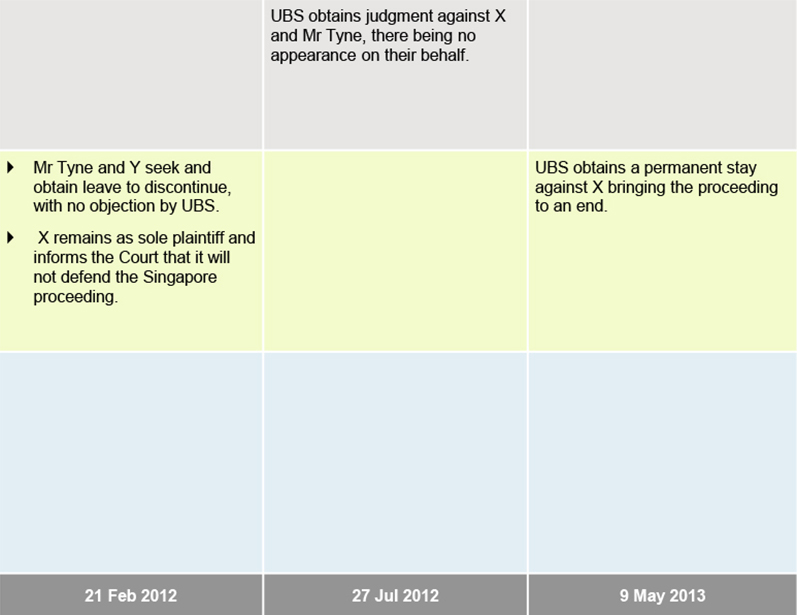

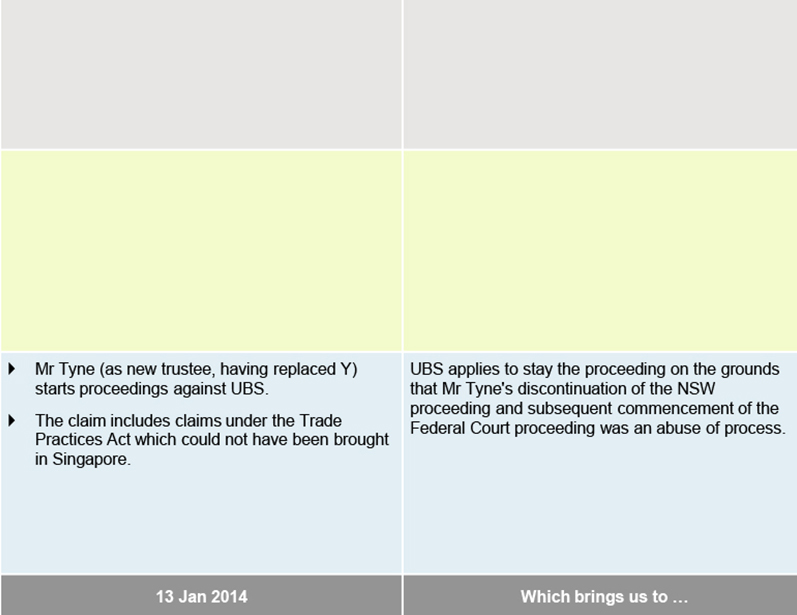

The litigation timeline in UBS v Tyne: Was there an abuse of process?

Litigation between Mr Tyne and UBS in Singapore and Australia spanned eight years and three courts. The key events are set out in the timeline below.

The question for the Court was whether Mr Tyne's discontinuance of one proceeding (which preserved his ability to rely on trade practices legislation in Australia) and commencement of another, amounted to an abuse of process. This turned on factors such as delay, wasted costs and public perception.

Those issues drew emphatic yet diametrically opposed views. The trial judge (Justice Greenwood) held that Mr Tyne's conduct amounted to an abuse of process. A majority of the Full Federal Court held that it did not. In the High Court, a majority (Chief Justice Kiefel and Justices Bell and Keane, and separately Justice Gageler) held that it did.

Was there "inexcusable delay"?

The High Court looked at established principles which suggested that in order to amount to an abuse of process, delay needed to be "appalling" or "inexcusable". One case on point involved a delay of 29 years.

The majority considered that to insist upon appalling or inexcusable delay was not in keeping with the overarching purpose, and the power to stay a proceeding could be exercised if there was substantial delay. They considered that the operative delay exceeded three years (seemingly the period between the start of the NSW proceeding in November 2010, and the start of the Federal Court case in January 2014) and that this was substantial and unacceptable.

In contrast, the minority (Justices Nettle and Edelman, and separately Justice Gordon) considered that the relevant test continued to be whether a delay was "appalling" and "inexcusable", and that the operative delay caused by Mr Tyne was only eight months (being the period between the permanent stay in May 2013 and the launch of the Federal Court proceedings in January 2014). They considered that the balance of the delay was caused by UBS having sought and obtained a stay of the NSW proceeding.

The public perception of the litigation

The majority considered that to allow the Federal Court case to proceed would cause a "right-thinking" person to believe that the administration of justice was inefficient and careless about public money.

The minority took a different view. They regarded the approach taken by Mr Tyne as reasonable and common sense, and that it would be understood as such by a right-thinking person. They considered it enabled Mr Tyne to take advantage of a legitimate juridical advantage, namely reliance on trade practices legislation which could not be done in Singapore.

The minority gave primacy to the requirement in section 37M that disputes be resolved "according to law". They considered that Mr Tyne was simply pursuing his legal rights, given that discontinuation does not operate as a release.

Where to from here?

Some may question whether the case represents judicial over-reach, particularly given the reference in section 37M to the just resolution of disputes according to law.

Lawyers and their clients will need to second-guess their first instincts in light of the harsh consequences which flow from a breach of the overarching purpose provisions. This will be challenging given that the High Court struck down conduct which was compliant with established legal principles and expressly permitted by the court rules.

Get in touch