Sales staff wanted, non-lawyers need not apply: navigating the maze of ACL consumer guarantees

The law on ACL consumer guarantees is laden with complexity and risk for suppliers and manufacturers dealing with customer complaints, but stops short of imposing a positive duty to advise customers of their rights.

The regulators have been active in policing the consumer guarantee provisions in the Australian Consumer Law (ACL). The decided cases show the perils of making unequivocal statements about the ambit of consumer rights (see, for example, Director of Consumer Affairs Victoria v The Good Guys Discount Warehouses (Australia) Pty Ltd (2016) 245 FCR 529 and Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Bunavit Pty Ltd [2016] FCA 6).

A recent case reaffirms this cautionary message but, importantly, suggests that the law does not require suppliers and manufacturers to actively educate consumers (Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v LG Electronics Australia Pty Ltd [2018] FCAFC 96).

Life's Good… or is it?

The ACL prescribes certain statutory guarantees which cannot be contractually excluded. They include guarantees that goods will be of acceptable quality and fit for their purpose (ACL sections 54 and 55).

In the LG case customers complained of defects in televisions which arose after the manufacturer's warranty had expired. The regulator alleged that statements made by LG in response to those complaints were misleading or deceptive under section 18 of the ACL.

The representations included statements that:

- the customers' rights were limited to the manufacturer's warranty;

- any assistance offered by LG after expiration of the warranty was a gesture of goodwill;

- LG would repair the televisions but the customers were not entitled to receive a refund.

The Full Federal Court held that the statements by LG that the manufacturer's warranty was the customers' only avenue of redress were misleading or deceptive given the rights conferred by the ACL. The Court otherwise dismissed the case on the basis that the other representations were merely statements by LG of what it was prepared to offer as part of the negotiations.

Navigating the legislative maze

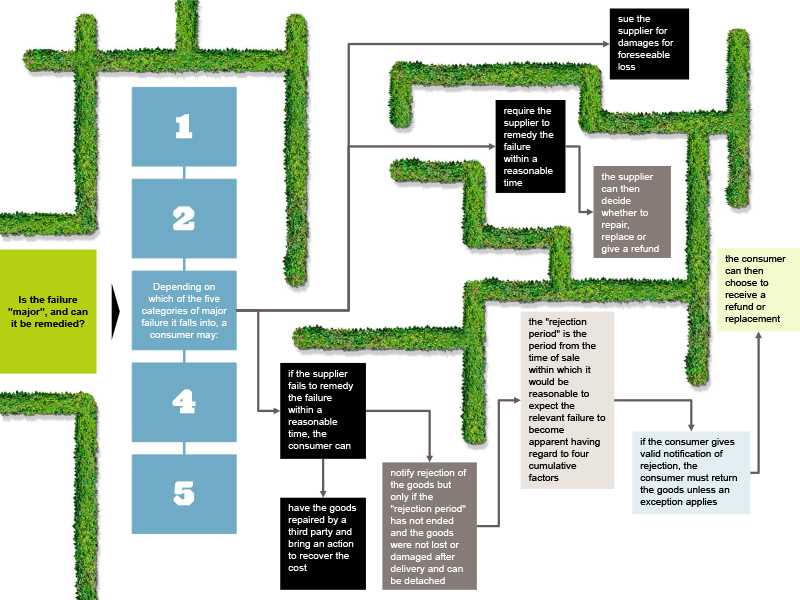

Those findings are unremarkable and consistent with prevailing authority. What is noteworthy about the case is that it appears to endorse the proposition that LG did not have a positive duty to advise customers about their rights, other than to correct any misconception which may have arisen during the commercial exchange. This outcome is fair and sensible given the onerous burden that would otherwise confront businesses. This is because a proper analysis of the ACL consumer guarantee provisions calls for consideration of complex and nuanced matters to answer even seemingly simple questions like: Can I get a refund?

No salesperson could reasonably be expected to explain this labyrinth to a consumer and the law rightly suggests that there is no obligation to do so. That said, commercial considerations would dictate the need to respond to customer queries. Simply remaining mute would be commercially untenable.

It seems that the best approach is to provide customers with accurate written material which summarises the operation of the ACL guarantees in plain English. Your discussions should then be framed with reference to that written material and conducted in a manner which would enable them to be characterised as commercial negotiations, as in the LG case.

Thanks to Lucy Cornford for her help in preparing this article.

Get in touch