Treasury publishes consultation paper on proposed merger reforms

Whether implemented in whole or part, the reform options outlined by Treasury are significant and set to have wide-ranging effects on the factors that deal teams and their advisers will need to take into account as part of any domestic or international cross-border merger involving a business with Australian operations or interests.

Treasury has released a consultation paper on the ACCC's proposed merger reforms released earlier this year in April, and called for input by 19 January 2024.

The consultation paper outlines three options for a revised merger clearance regime and options for changes to the current merger control test that the ACCC (and a Court if a court-enforcement model is retained) must consider in deciding if a merger is prohibited by section 50 of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (CCA).

What policy options does Treasury outline?

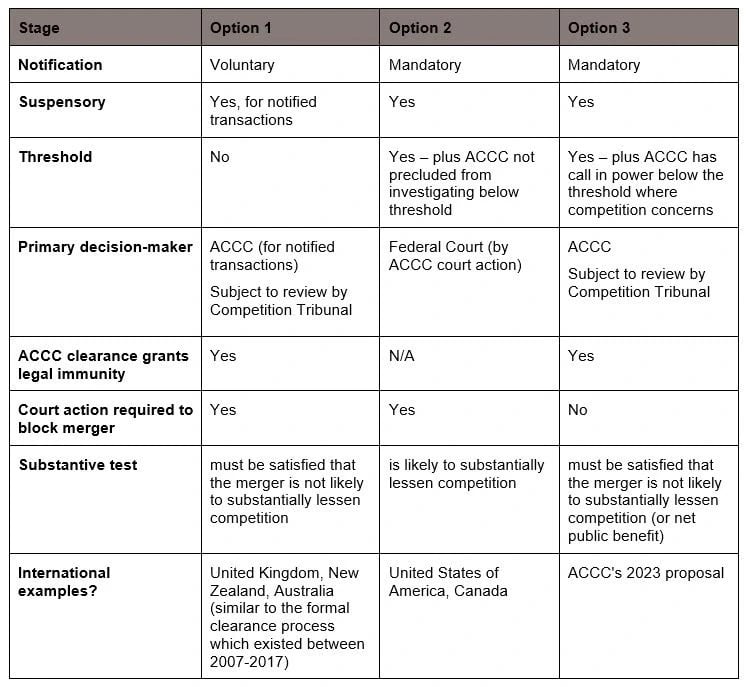

Treasury proposes three policy options for a new merger clearance regime:

Option 1 – A voluntary formal clearance regime where businesses could choose to notify a merger and the ACCC could grant legal immunity from court action under section 50 of the CCA if the merger would not be likely to substantially lessen competition. The ACCC's decision would be subject to review by the Competition Tribunal, but if the ACCC declined clearance and the parties sought to proceed with the merger, the ACCC would need to commence legal action in the Federal Court to prevent it going ahead – the ACCC would not be sole decision-maker.

Option 2 – A mandatory suspensory notification regime whereby mergers above a certain threshold would require notification to the ACCC. Transactions would be suspended whilst the ACCC conducts its assessment. Similar to Option 1, to prevent an anti-competitive merger the ACCC would need to prove to the court that the merger would be "likely to substantially lessen competition" – the ACCC would not be sole decision-maker.

Option 3 – which the ACCC wants – a mandatory formal clearance regime where the ACCC is the main decision-maker, not the courts. This would require compulsory notification as well as a discretionary power for the ACCC to "call in" transactions below the relevant threshold where there are competition concerns. Like in Option 1, clearance would provide legal immunity from court action under section 50 of the CCA. The legal test to be applied under this model is similar to Option 1 in that the ACCC "must be satisfied the merger is not likely to substantially lessen competition (or net public benefit)". There would be limited merits review to the Competition Tribunal. The role of the Federal Court would therefore be much reduced under this model.

Treasury sees "emerging concerns"…

At the outset, Treasury states:

"Most mergers do not raise competition concerns. However, a small proportion of proposed mergers, if allowed to proceed, would be anti-competitive. Merger control is about maintaining competitive market structures which lead to better outcomes for consumers… Merger control regimes therefore need to be risk-based, devoting more regulatory resources to those that are more likely to be anticompetitive and therefore more likely to cause harm to the community."

Treasury cites evidence that the intensity of competition has weakened across many parts of the economy, accompanied by increasing market concentration and mark-ups in many industries. Productivity growth in Australia has also slowed and acquisitions of minority interests, interlocking directorships and changed incentives for competing firms to compete are an increasing concern.

Treasury also notes international evidence in which:

- doubt is cast over the frequency and extent to which mergers give rise to efficiencies, and whether such efficiencies are then passed on to consumers; and

- retrospective econometric studies tend to suggest a trend towards "a surprisingly large proportion of mergers resulting in anticompetitive effects (increased market prices and/or reduced activity)."

However, there is not any clear data linking increasing concentration in Australia to problems with the merger review processes.

So, is there a problem with the current merger control system?

In framing its consultation, Treasury notes the ACCC's concerns that merger clearance is:

- "skewed towards clearance" because of the current system's emphasis on inherently unpredictable counterfactual analysis, and the weight given by the Court to evidence of merger parties' senior executives in circumstances where there is information asymmetry between merger parties and the ACCC, and/or third parties are reluctant to give evidence in Court; and

- not as effective as it needs to be due to the conduct of merger parties who, for example, threaten to complete a merger before the ACCC completes its review, fail to notify the ACCC at all, and/or provide insufficient or inaccurate information to the ACCC which prevents the ACCC completing its review.

However, other commentators have noted merger control continues to be complex because a judgment is always required about the future state of competition, and the ACCC's economic theories have not always found favour with the Federal Court.

Further, the ACCC could do more with its existing information gathering powers to ensure it obtains all necessary evidence in assessing a proposed merger.

The consultation paper also acknowledges the difficulty in obtaining evidence as to the number of mergers which are completed without notifying the ACCC, particularly those which would require notification under the proposed thresholds. This in turn also raises difficulty in determining whether those mergers are likely to be problematic under section 50 of the CCA in the first place.

While the consultation paper outlines a range of reform options, Treasury's Option 3 is the closest to the ACCC's proposed option, and involves a mandatory and suspensory regime where:

- the substantive test is that satisfaction on the balance of probabilities that the merger is not likely to substantially lessen competition (or net public benefit);

- the ACCC is the primary decision-maker (not the Court or Australian Competition Tribunal); and

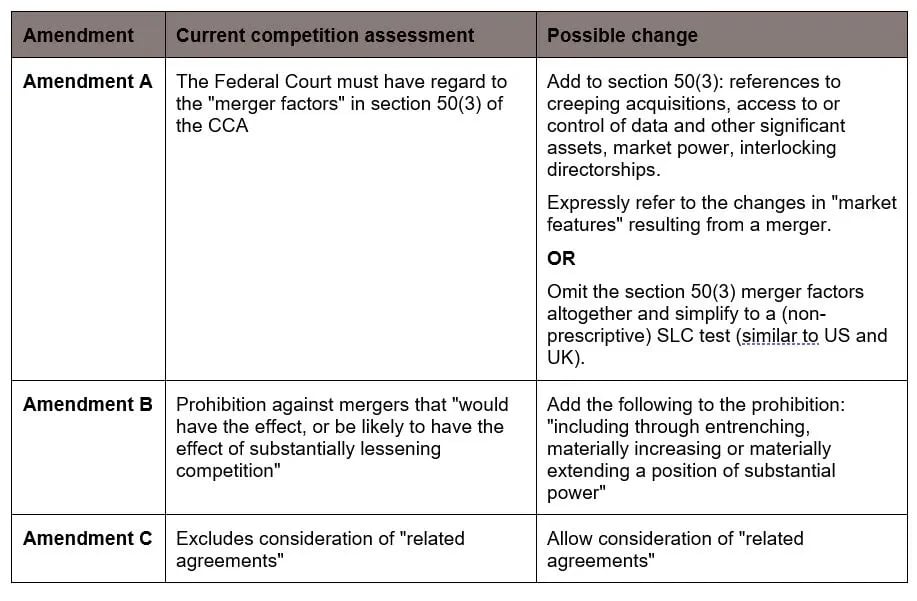

- the merger assessment criteria are changed by:

- adding specific factors which consider creeping acquisition, loss of potential competition, access to or control of data and other significant assets, market power and interlocking directorships;

- expressly referring to the changes in market features (or structural changes) resulting from a merger;

- omitting the current merger factors in section 50(3) of the CCA (seemingly as an alternative to (i) and (ii) above);

- expanding the (current) substantial lessening of competition test to include transactions that "entrench, materially increase or materially extend a position of substantial market power";

- specifying that the assessment should consider related agreements between merger parties (such as non-compete agreements or supply agreements post-merger).

Options 1 and 2 are described by Treasury as judicial enforcement merger control options relying on litigation by ACCC in the Federal Court to stop a merger considered by the ACCC to be anti-competitive.

Option 3 is primarily an administrative model where the ACCC is the decision-maker and its decision would only be reviewable by the Australian Competition Tribunal, with the Federal Court providing judicial review (of the Tribunal's decision) not any merits review of the merger. This would be a significant departure from our current system, where it is for the Court and not an administrative decision-maker to decide whether a merger breaches section 50.

The proposed models draw upon international examples. Set out below is a high-level comparative summary.

Other changes to the merger control test

In addition to the above proposals, the consultation paper identifies three further amendments which Treasury proposes for reform to the merger control test. These proposed amendments incorporate elements which are largely familiar from recent ACCC commentary and recommendations made by the ACCC in its Digital Platforms Services Inquiry.

Set out below is a summary of those proposed amendments (with the ACCC position stated by Treasury to be that it favours the adoption of all proposed amendments).

What will be the threshold for mandatory notification?

Treasury does not put forward any specific threshold for consultation but does note the prior threshold proposed by the ACCC:

"[the threshold] could be set with reference to the value of the proposed transaction, the size of the business being acquired globally and/or within Australia, or a combination of these factors. Based on our preliminary analysis of past ACCC informal public reviews, an acquirer or target turnover threshold of $400 million or global transaction value threshold of $35 million could be appropriate."

Key takeaway

Submissions on the consultation paper are due on 19 January 2024. Whether implemented in whole or part, the reform options outlined by Treasury are significant and set to have wide-ranging effects on the factors that deal teams and their advisers will need to take into account as part of any domestic or international cross-border merger involving a business with Australian operations or interests.

Get in touch