Competition law “not an immovable obstacle” in the move toward a sustainable economy

The ACCC has recently published much anticipated consultation draft guidelines to help businesses navigate competition law risks when collaborating over environmental and sustainability initiatives. From a policy standpoint, the ACCC’s “intention in developing this guide is to make it clear competition law should not be seen as an immovable obstacle for collaboration on sustainability that can have a public benefit.”

The release is timely – in June Federal Treasurer Jim Chalmers announced a sustainable finance roadmap designed to maximise the investment and economic opportunities of the net zero transformation. As businesses take up these opportunities and work toward achieving net zero goals, clear guidance on competition law compliance is needed to avoid unnecessarily hampering progress.

The consultation draft guidelines follow the ACCC’s announcement in March that competition and consumer issues relating to sustainability issues are a priority in its enforcement agenda for the year, and its release of revised greenwashing guidelines in December 2023.

What you need to know about the ACCC’s draft “Sustainability collaborations and Australian competition law: A guide for business”

- Sustainability initiatives must comply with competition laws. The Competition and Consumer Act (CCA) prohibits competitors from engaging in cartel conduct (such as price fixing, restricting outputs, allocating customers, suppliers or territories, and bid rigging). The CCA also contains broad prohibitions on arrangements or conduct that have the purpose, effect or likely effect of substantially lessening competition in any market.

- The legal position has not changed. It is still the case under the CCA that environmental and sustainability goals cannot be used to hide illegal conduct, and the penalties for breaching these prohibitions are significant. For corporations, the maximum civil penalties for breaches are the greater of AUD 50 million, three times the reasonably attributable benefit, or 30% of adjusted turnover during the relevant period. Cartel breaches are also criminal offences.

- However, the ACCC’s draft guidance recognises that there may be legitimate reasons for businesses to coordinate conduct in order to achieve sustainability goals and outlines some examples of higher and lower risk collaborations.

- Where sustainability collaborations involve a potential breach of the CCA, businesses can seek authorisation from the ACCC, which provides legal immunity. Authorisation can be granted if the ACCC is satisfied that the public benefits (including sustainability benefits) of the initiative or conduct will outweigh the public detriments. Where in doubt, seek legal advice to discuss your options.

- The ACCC is seeking feedback on the draft guidelines including whether they improve businesses’ understanding of competition law risks, and provide sufficient information on what steps to take. The consultation period ends on 26 July with the ACCC aiming to publish the final guidelines in late 2024.

The competition law risks of sustainability collaborations

Sustainability collaborations between competitors (or potential competitors) may risk breaching the prohibitions on cartel conduct. Collaborations that relate to or affect pricing, markets that parties will/ won’t operate in, customers or suppliers parties will/ won’t deal with, the nature of the parties’ outputs or inputs, or bids for tenders, are high risk areas.

Regardless of whether the parties to the collaboration are competitors, sustainability collaborations may also breach other prohibitions in the CCA if they involve conduct such as a “concerted practice” or contracts, arrangements or understandings that have the purpose or likely effect of substantially lessening competition.

The draft guidelines note that collaborations are more likely to substantially lessen competition where they prevent businesses from competing effectively, make new entry or expansion more difficult, and/or involve sharing of competitively sensitive information. A collaboration is less likely to substantially lessen competition where businesses are not competitors or likely competitors, make decisions independently, are free to innovate and choose who they buy from and sell to, and do not share competitively sensitive information.

Sustainability collaborations may be legitimate

The draft guidelines recognise that there may be legitimate reasons for businesses to collaborate to achieve sustainability goals, for example, where individual businesses do not have the incentive or ability to address the environmental impact on their own. High-level examples given include:

- an individual business has insufficient volumes to justify the related size of an investment

- an individual business acting on its own is unable to achieve the beneficial environmental outcome in a timely manner

- the arrangements are not in the business’ best financial interest, but it is nonetheless beneficial to society more generally

- a business acting on its own would be at a competitive disadvantage relative to its rivals, including as a result of other businesses free riding on its efforts.

These legitimate goals do not of themselves legalise collaborations, but they may assist in obtaining authorisation from the ACCC.

High-risk and low-risk sustainability collaborations

The draft guidelines set out a number of examples of high- and low-risk collaborations (however each case will require individual assessment on its facts). High-risk collaborations that are likely to breach the CCA unless a net public benefit can be shown include where:

- businesses that compete to acquire a certain type of input, agree to only buy the input from suppliers that meet a particular sustainability criterion;

- suppliers agree to charge a levy on the sale of their products to customers to fund an industry recycling scheme at the end of their products’ life; or

- rival manufacturers agree to use a new technology in their production process and to stop using older technology that emits more pollution.

On the other hand, examples of low-risk sustainability collaborations that are unlikely to require authorisation would include:

- jointly funded research into reducing environmental impact;

- pooling information about suppliers such as environmentally sustainability credentials – provided there are no agreements to purchase from/ boycott from particular suppliers nor involve sharing of competitively sensitive information;

- voluntary industry wide emissions reduction targets such as pledges to work towards a reduction; or

- discussions about sustainability that lead to independent decisions about using a sustainable input.

The authorisation process under the Competition and Consumer Act

Authorisation is a statutory process under the CCA through which conduct that might breach competition laws can be authorised by the ACCC if it is satisfied that there are public benefits that outweigh the public detriments. The concept of "public benefit" is very broad and has been interpreted as any benefit to society at large. It isn’t, for example, necessary that the benefits accrue to the same group of customers that might be harmed by the anti-competitive conduct – but the benefits must arise from the conduct in question.

Environmental public benefits have frequently been included, among others, in the list of benefits in authorisation applications and the ACCC has made clear that sustainability will be an important consideration going forward.

In the context of merger authorisation, the ACCC has also showed it was willing to entertain environmental benefits as delivering a net public benefit in its decision to grant merger authorisation to Brookfield/MidOcean’s proposed acquisition of Origin Energy (June 2023).

Previous authorisations which involved environmental benefits have included conduct involving coordination of recycling levies, joint purchasing of renewable energy and joint tendering that facilitated investment in recycling among other sustainability benefits.

Authorisation is a public process and typically takes around six months, but businesses can request an urgent interim authorisation so that they can start collaborating, pending the ACCC’s final decision.

Assessing the risk and getting ACCC authorisation for sustainability collaborations

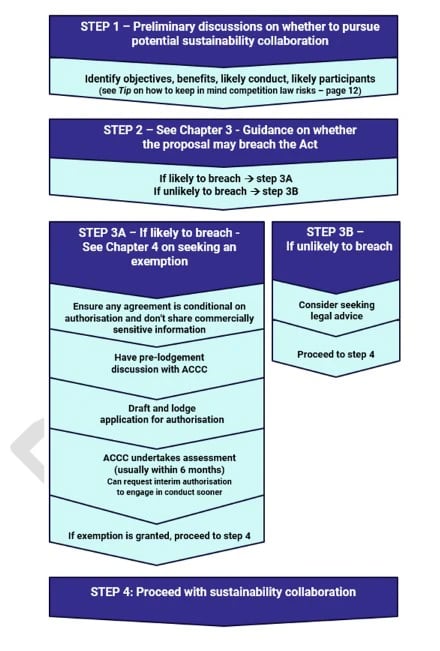

The draft guidelines give two helpful pieces of advice. First, it recommends a decision-making framework:

The ACCC also sets out a number of practical tips for making sure the authorisation process is as smooth and efficient as possible:

- Informally discuss the collaboration with the ACCC before lodging. The ACCC can provide guidance on whether authorisation may be suitable or other exemptions should be considered. The ACCC can also provide guidance on information to provide in the application, provide feedback on a draft application, and guide parties on the process and likely timeframes.

- Clearly define the arrangements. Any application for authorisation will need to accurately describe the scope of the conduct to be authorised, and specify all provisions of the CCA for which authorisation is sought.

- Substantiate sustainability claims. Applications should clearly explain how sustainability benefits (and any other benefits) will result from the collaboration and why they are likely to occur (not just mere possibilities). Parties should provide clear evidence and quantify the benefits where possible. Any methodologies, assumptions and sensitivity testing that underly the quantification should be provided. Where relevant, include details of any domestic or international standards that the proposed collaboration is designed to achieve or exceed.

- Explain why the collaboration is needed and proportionate. Parties should explain why the businesses cannot individually address the concern. Parties should also show that the collaboration is proportionate – ie. the benefits cannot be achieved by using measures that are equally effective but less restrictive.

- Set out measures that will ensure the benefits will be achieved. ie. what, if any, transparency and reporting measures will be implemented, and what steps are in place to identify and address any issues.

Sustainability collaborations are only going to increase, and the risks of breaching competition law are clear. Given the brief consultation period and the ACCC’s intention to have these guidelines finalised soon, businesses should be considering these as close to final, and begin reviewing their own practices to ensure they don’t make a costly mistake.

Get in touch